A Critique of Bill Maher’s Recent Segment on Indigenous Peoples

A View-from-the-Shore Assessment

The sight of three Native peoples of Southern California being acknowledged during this year’s Oscars evidently got under Bill Maher’s skin. His often-condescending style became even more pronounced than usual.

He seemed to suggest that a mere twenty-six words of respect expressed in honor of Indigenous peoples of southern California during the Oscars illustrates the kind of behavior that cost the Democrats the recent presidential election.

Here’s how Maher expressed a “new rule” for “the Democrats”: “[I]f you ever want to win an election again, the absolute, most important first step is stop doing this.” (emphasis added). He then cut to a clip of Julianne Hough saying during the Oscars: “We gather in celebration of the Oscars on the ancestral lands of the Tongva, Tataviam, and Chumash peoples, the traditional caretakers of this water and land.”

In response to those few words, Maher declared, “Yeah, I don’t know if we’re still saying ‘cringe’, but if we are, that’s this [statement by Ms. Hough]. I said it before and I’ll say it again, ‘either give the land back or shut the fu*k up.”

Since no land is likely to be handed over to any Indigenous peoples in California any time soon, this leaves us with Maher’s second option when it comes to Indigenous lands: Silence.

Also according to Maher, it is not necessary to acknowledge Indigenous peoples and their traditional homelands in California, because, as Maher put it, Indigenous peoples of long ago were “in fact, more full of sh*t than humans today.”

From a Native perspective, the title of Maher’s segment, “Guilt by Civilization,” evokes the idea of guilt for well-documented genocide waged against the original nations and peoples of California.

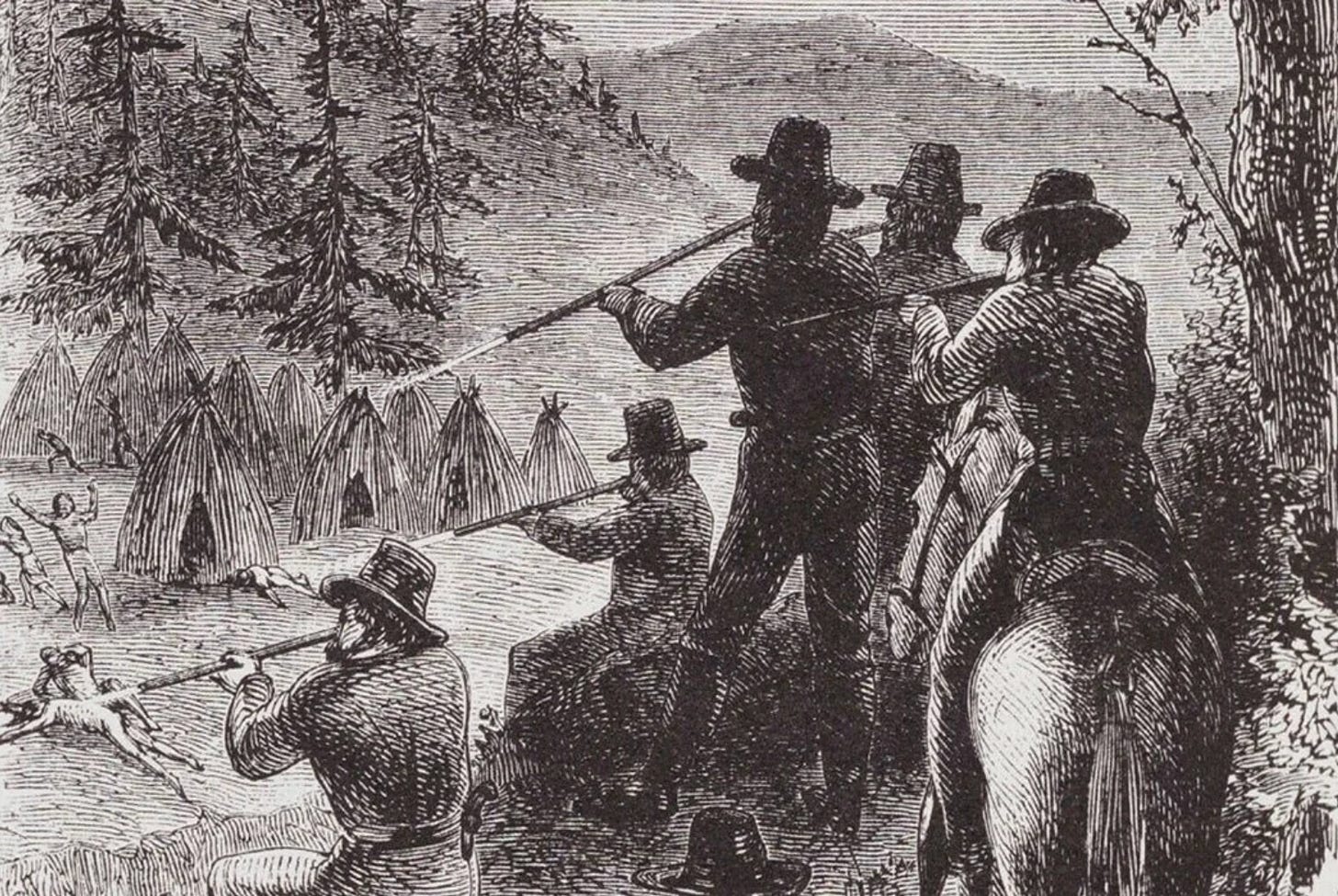

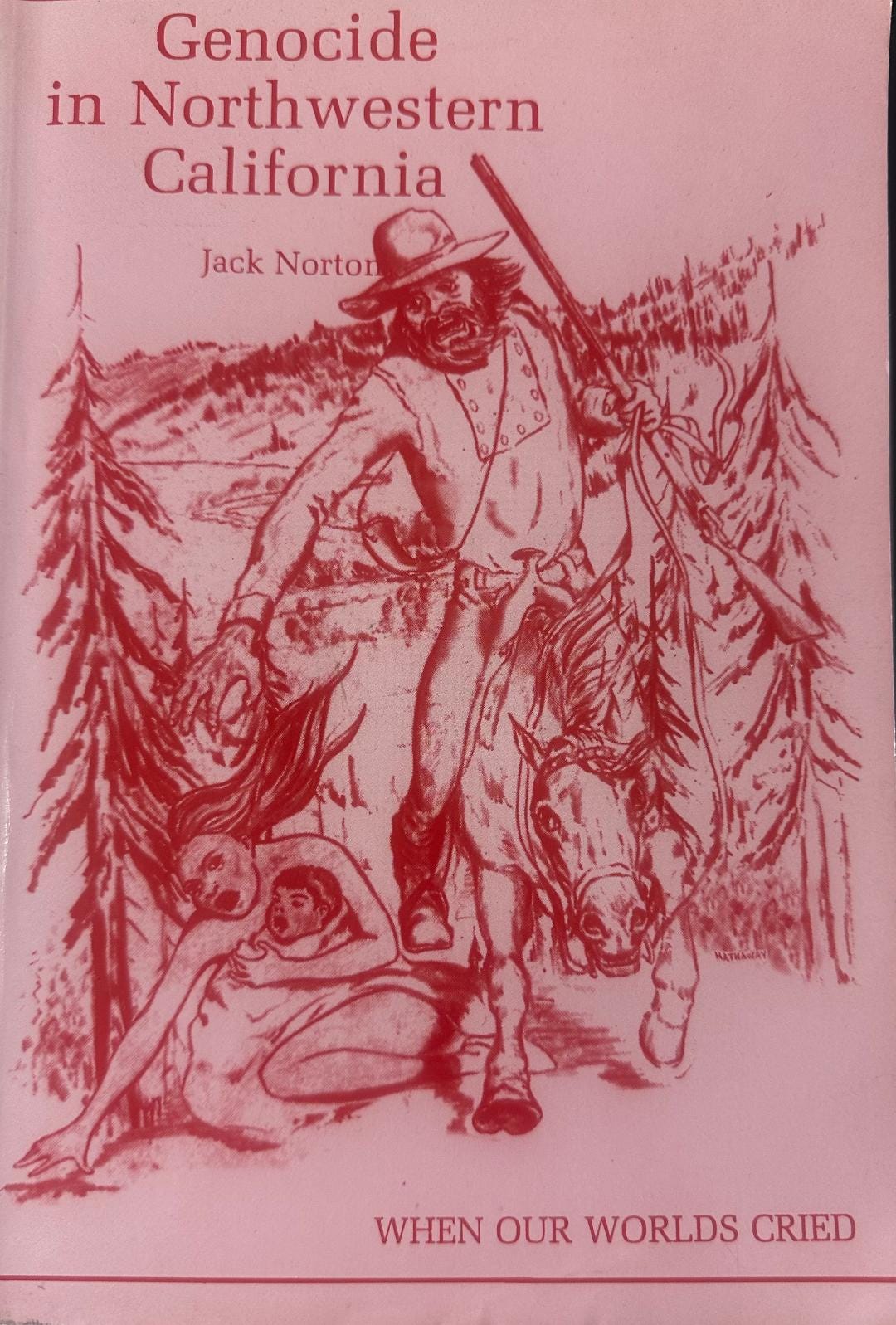

We see this history recounted in Benjamin Madley’s An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe 1846-1873 (Yale University Press, 2016) and Brendan Lindsay’s Murder State: California’s Native American Genocide 1846-1873 (University of Nebraska Press, 2015). We can also add Jack Norton’s 1979 Genocide in Northwestern California, published by Rupert Costo’s Indian Historian Press. But Maher didn’t go down this road.

Perhaps the subtext of Maher’s sneering, mocking segment was to encourage the American people to refuse to admit that American civilization [i.e., domination] bears any responsibility for the devastation it has inflicted on Indigenous peoples across the continent.

As if to say: “Our American society has nothing to be ashamed of or feel guilty about for helping itself to, and enriching itself by means of, millions of acres of Indigenous peoples’ lands in California now worth trillions of dollars. We have no obligation to acknowledge the genocide Indigenous peoples experienced as the result of a system of domination that was brought by ship to this continent and asserted first by the Spanish crown, then by the empire of Mexico, and then by the American empire.”

Maher also said: “Today’s Hippies love to harp on how the 1950s was backward, and 1950s was backward as every past era was.” Evidently Maher thought that resurrecting the Hippies of the late 1960s and early 1970s would work for his comedy bit by drawing a connection between the 1950s and the 1550s.

Maher continued by asking mockingly, [T]oday’s Hippies “see Indigenous life in the 1550s [laughing] as the pinnacle of enlightenment?” The question mark and laughter were evidently intended to make fun of the idea that Indigenous peoples had a way of life that many European explorers and intellectuals admired.

But in his book New World’s for Old: Reports from the New World and their effect on the development of social thought in Europe 1500-1800 (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1986) William Brandon says that one of the most notable aspects of Native societies was a “preoccupation with group relationships, lack of interest in acquisition of property, and frequent lack of central authority resulting in a seeming masterlessness,” meaning, a lack of dominium (i.e., domination).

Brandon examines the deep influence that early reports of Native societies had on the peoples of Western Europe. “One of these American Indian influences,” writes Brandon, is “the idea of liberty.”

His examination of the historical record leads him to conclude that “our current idea of liberty developed much of its modern sense in Europe and America in the three centuries following European contact with the New World.” It is Brandon’s assessment that “These reports on the New World headlined notions of liberty, a popular liberty involving elements of equality and masterlessness.”

But what is Maher’s ill-informed assessment of the free and independent ancient lifestyle that Indigenous ancestors lived for thousands of years on vast amounts of their own lands and waters? In Maher’s estimation, the free way of life of Indigenous peoples was no better than the lifestyle of poverty-stricken and hungry homeless people who are living on the streets of Los Angeles without one square inch of land to call their own.

In Maher’s view, the free way of life of Indigenous ancestors was analogous to “living outside, foraging for food, and washing your clothes in a pond.” “We have that today,” he said, “It’s called being homeless, and it sucks.”

How odd to think of Indigenous peoples as living an inferior lifestyle by living a spiritual and ceremonial way of life, free and independent on their own lands, with pure air, pure food, and pure water. True, they were living without many of the “advances” and “gifts” of “civilization’s progress,” such as glyphosate, PFOAs, lead, mercury, and massive amounts of toxicity from thousands of chemical pollutants.

Indigenous peoples didn’t have posted cancer warnings on the land, hundreds of chemicals in the umbilical cord blood of pregnant women, superfund sites, radiation poisoning from the testing of nuclear bombs, gain-of-function bioweapons, and the toxic fallout from eight hundred to a thousand lithium-ion electric batteries that burned at Moss Landing in the Carmel/Monterey area, releasing massive amounts of pollutants that rained down on the land, air, water, animals, and crops.

Maher continued his ridicule of Indigenous peoples by stating: “It was no fun being alive before anesthetics, or refrigeration, or germ theory, or the fork, or facetime; socks are great too.” Maher’s words echo a variety of slurs about Indigenous peoples from the past such as “dumb Indians,” “barbarians,” “a state of barbarism,” “heathens,” “pagans” “infidels,” “savages,” “backward people,” “digger Indians,” and so forth.

And if there was nothing appealing about the traditional American Indian way of life, then why did the vast majority of “white captives” during colonial times run back to live with our Native ancestors after they were returned to their “civilized” society? Many observers, including Benjamin Franklin, commented on this phenomenon.

Maher also stated that Indigenous peoples were “quite warlike” before they were invaded by Europeans. William Brandon notes that early European observers of Native societies arrived at a different conclusion: “From Vespucci onward, Europeans remarked on the motives, so seldom ‘serious’ from a European standpoint, for so many Indian versus Indian conflicts. . . Even territorial confrontation seems to have resulted, as often as not, in the supine withdrawal of one side or the other; ‘the history of Indian America is riddled with instances of inexplicable (to us) pacifism.”

As further response to Maher’s comment about “warlike” peoples, we may once again quote William Brandon: “Reliable estimates put at about seventy million the figure of those dead through war, revolution and famine in Europe and Russia between 1914 and 1945 [a mere thirty-one years] . . . Much of the crisis of identity and society that has overshadowed twentieth-century history comes from an impulse toward totalitarian politics.” (emphasis added)

Even assuming that some Indigenous peoples were “quite warlike”, I wonder about the scale of those wars or conflicts, and how they might compare to the track record of the United States—the number of people estimated to have been killed in wars by the United States over the course of its existence?

According to Michel Chossudovsky at Global Research, that record of deaths has reached some twenty million people after WWII. Perhaps that’s a sensible focus for “guilt by civilization.” That’s ninety million humans sacrificed on the Altar of War from 1914 to 2025 in just the above two examples. Now that’s quite warlike.

Thanks Peter for your strong support!

Thanks Steve for another clear explanation of history and a strong critique of the stupidity that passes for Hollywood humor.