The Fabrication of a Reality of Domination

How Sacred Native Spaces Became Gated and Commercial Places

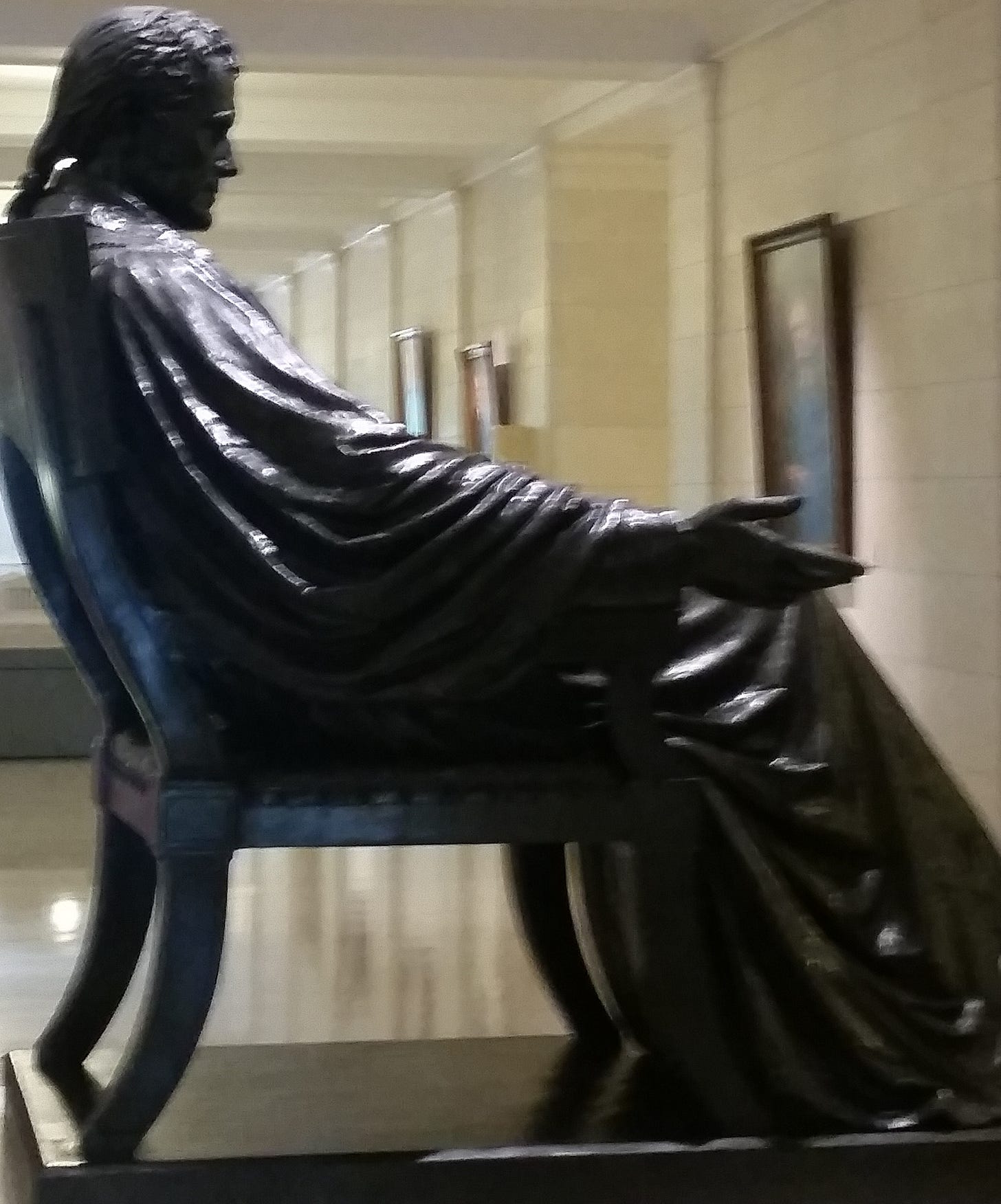

“Majesty of Law” Statue with the Sword of Justice, Outside the U.S. Supreme Court Building

(Photo by Steven Newcomb)

Centuries ago, a “discovery” of an inhabited country was the result of a successful seafaring voyage, undertaken to identify geographical areas, which the voyagers—before they set sail—had assumed to exist somewhere out there across the ocean.

The precise location of those unknown places were as yet unidentified when those first ships set sail; but the voyagers ventured forth with a view-from-their-ship, in search of any as yet unidentified islands or continents. Once any geographical areas were identified it was then possible for the voyagers to assert a right of domination over those previously unknown places, and gradually, by means of bloody “tried and true” processes of domination, sacred Native spaces were claimed as the invaders’ fenced, gated, and commercial places.

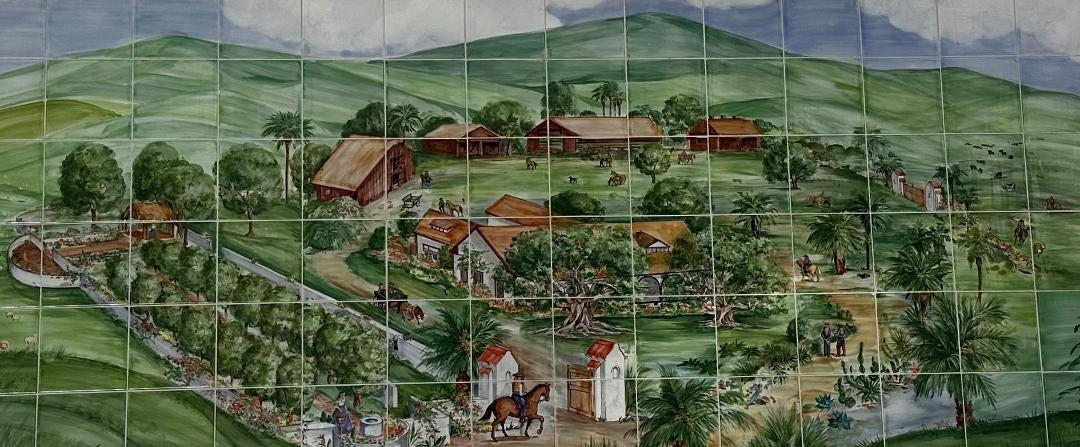

Tile Art of Los Alamitos Rancho, in Long Beach, CA (Photo by Steven Newcomb)

The Supreme Court ruling that best explains this process is Johnson v. McIntosh. For the average person, and even for many attorneys, the language of the Johnson ruling is difficult to decipher. Fabricate is one word that comes to mind when I think about what Chief Justice Marshall accomplished by issuing the Johnson decision on behalf of a unanimous Supreme Court.

One meaning of the verb “to fabricate” is “to form by art and labor.” If we say that someone or a group of people have artfully “fabricated a pretension,” we could be intending to say that they have mentally and metaphorically made up a claim or assertion, which could be true or false.

The “pretension” could be formed by a single person or a group of people pretending that something is true, while knowing it isn’t. To pretend can also mean “to make a show or profession of something falsely or with an intent to deceive; feign; sham.” Such terminology seems fitting with regard to the Court’s opinion in the Johnson ruling.

Toward the end of Johnson, we find Chief Justice John Marshall referring to an “extravagant pretension” of “converting the discovery of an inhabited country into conquest [a claimed right of domination].” How clever on Marshall’s part: the verb “to convert” can be thought of as, “to turn something from one form or type into a different form or type.” This involves a kind of linguistic alchemy or “magic.”

Sometimes the linguistic alchemy becomes explicit and overt. The opening of a multi-layered sentence from the Johnson decision provides an example. It reads: “However extravagant the pretension of converting the discovery of an inhabited country into conquest may appear . . .”

Translation: It may appear extravagant [unreasonable] to pretend to convert the identification of an already inhabited country into a claim of a right of conquest [domination] over that country.

Marshall’s use of the term “converting” leads to the word “conversion,” which Ballentine’s Law Dictionary defines in a manner that, not surprisingly, brings us once again to the theme of domination: “Conversion”: “a distinct act of dominion [domination] wrongfully asserted over another’s personal [or an entire People’s] property in denial of or inconsistent with his [their] title or rights therein.”

“Chief Justice John Marshall and His ‘Laptop’” at the U.S. Supreme Court (Photo by Steven Newcomb)

The chief justice, on behalf of a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court, was writing about an “act of domination wrongfully pretended or assumed” by voyaging and invading foreigners over a newly identified, but already inhabited, geographical location.

The pretension Marshall refers to involves pretending that the identification of an already inhabited place (foreign voyagers seeing that place for the first time) is equivalent to the “conquest” of that place, meaning equivalent to a victory [domination] over it and over the Native peoples already living there. This is what Marshall termed “extravagant,” i.e. outlandish.

Marshall conceded that it might appear unreasonable for the U.S. government to pretend that seafaring strangers seeing (‘laying eyes on,’ so to speak) an already inhabited place for the first time amounted to the “conquest” of that place. When we think about it, though, it is at this point that the newly identified place ‘enters’ the domination language and consciousness of the foreign voyagers, and, conversely, it is the point at which the domination consciousness and language of the foreign voyagers ‘enters’ what is from the viewpoint of the original nations and peoples ‘Sacred Native Spaces’.

As a result, that entire geographical area becomes ‘subject to’ the domination language, mental activity, and decision-making of the invaders, a language, mental activity, and decision-making that the original nations and peoples are not able to access or control.

It might also seem unreasonable (“extravagant”) for the highest court of the United States to use the assertion that “discovery = conquest” as a rationale for regarding the seafaring foreigners, and their descendants [e.g. the United States], as having the right to assert a perpetual right of domination over the continental location their ancestors had identified centuries earlier.

But here’s the kicker: If such a pretension “has been asserted . . . and afterwards sustained,” said Marshall, and “if a country has been acquired and held” on that basis, and “if the property [“despotic dominion”] of the great mass of the community originates in it, it [the pretension of having a right of domination over that country] becomes [can be treated by the descendants of the invading foreigners as] the law of the land” which “cannot be questioned.”

For the purpose of the Johnson decision, the Supreme Court had decided to treat the seafaring foreigners’ invading claim of a right of domination as the law of the land which could not be questioned by the courts eventually formed by the descendants of the seafaring foreigners.

“So too,” Marshall added, “with respect to the concomitant [accompanying] principle that the Indian inhabitants are to be considered [mentally regarded] merely as occupants, to be protected, indeed, while in peace, in the possession of their lands, but to be deemed incapable of transferring the absolute title to others.” (The phrase “protected, indeed, while in peace” suggests that a violent response would be justified if the Native peoples attempt to protect their lands or to defend themselves from efforts to violently eject them from their lands).

The investigative trail leads us to the website of the U.S. Supreme Court where we find an explanation of the “Primary Holding” of the Johnson ruling, which I’ve written about previously: “When a tract of land has been acquired through conquest [domination], and the property [claimed right of domination] of most people who live there arise from the conquest [the domination], the people who have been conquered [forced to live under and subject to domination] have a right to live on the land but cannot transfer title to the land.”

Compare Marshall’s wording in the ruling “but to be deemed incapable of transferring the absolute title to others,” to the Supreme Court’s explanation of its “Primary holding” in Johnson: to wit, because of “conquest” [domination] the Native people, who are presumed to be “conquered have a right to live on the land but cannot transfer title to the land.”

Returning now to Marshall’s wording, he continued:

“However this restriction may be opposed to natural right, and to the usages of civilized nations, yet if it be indispensable to that system under which the country has been settled, and be adapted to the actual condition of the two, it may perhaps be supported by reason, and certainly cannot be rejected by courts of justice.”

Let’s now apply my Domination Translator to the above paragraph:

“However [even though] this restriction [of the Native peoples to a title of occupancy] may be opposed to natural right [the liberty of our original Native nations and peoples], and to the usages of civilized [dominator] nations, yet if it [that restriction] be indispensable to that system [of domination] under which the country has been settled [dominated], and be adapted to the actual condition of the two people [dominators and dominated], it [the reduction to a mere right of occupancy] may perhaps be supported by reason, and certainly cannot be rejected by courts of justice.”

From Marshall’s words, we are able to grasp the following meaning: The people who called themselves “Christian” and “European” purported to mentally and metaphorically “give” (ascribe to) themselves a right and title of domination to the continental lands they were claiming on our part of the planet.

At one point in the Johnson ruling, Marshall said “that discovery gave title to the government by whose subjects or by whose authority it [the ‘discovery’] was made,” “against all other European governments.” (emphasis added)

Few people seemed to have noticed that this “Indian title of occupancy” is also a pretension mentally fabricated by Marshall and the Supreme Court. That idea of “occupancy” was part of what Marshall identified as being among “those principles also which our own government has adopted in the particular case and given us [to the Supreme Court] as the rule for our decision.”

Here’s the thing: What Marshall called “discovery” (i.e. a form of knowledge) was the activity of the mentality and consciousness of the Christian Europeans, “discovery” was not a sentient being. “Discovery” could not have given a title to anyone. There was no physical person named “discovery,” who “gave” anyone a title to the land.

However, flesh and blood humans could and did use their mental faculties to imagine themselves as having “a right and title of domination” over and to the already inhabited lands of Native nations and peoples. They could use their spoken language and written word to form “deeds” and other documents to conjure that form of reality into existence. This process of mental activity and conjuring was how they helped themselves to the lands and waters they had identified by sailing from western europe across the ocean to Turtle Island (“North America”) and that they were now claiming as their own.

And once they had imagined and acted upon such scenarios, within their mental world they were then able to metaphorically treat their pretensions as if they were physically true, and, when they deemed it necessary, they were perfectly willing to back their imperial project with lethal force. As a result, we live today in a fabricated mental and physical reality of domination.

Thank you for your comment, Darcia. I appreciate you reaching out.

Wow. This is the best analysis of the Johnson ruling I have read.